Ever wonder why store-bought mac and cheese or lemonade appear so bright, while the homemade versions are duller in color? The answer lies in artificial colors or synthetic color additives that have been added to food products to enhance their visual appeal and make them appear more enticing. Many of the natural colors found in foods are lost or muted as foods are commercially processed, resulting in products with a duller hue. To mask this and make these products look more attractive to consumers, food manufacturers turn to artificial colors to improve the product’s appearance.

The “Why” of Artificial Colors

These additives confer absolutely no nutritional value to the products, are completely unnecessary, and are found predominantly in foods marketed towards children who are drawn to the eye-popping colors. In addition to foods such as breakfast cereals, juices, candies, and snack items, artificial colors also lurk in foods where you may never suspect them such as soups, salad dressings, yogurts, and baked goods. They are also used to make consumers think that foods contain more expensive natural ingredients such as real fruit, rather than cheaper synthetic ingredients. Artificial food colors are generally used in lower quality food products that typically contain a host of other hard-to-pronounce chemical ingredients.

A Brief History

Food dyes or color additives date back for thousands of years. The Egyptians used color additives naturally derived from vegetable and mineral sources to impart color to make-up and wine. Artificial or synthetic food dyes were first discovered in the mid-1800’s and proliferated rapidly over the next century. These agents had more intense coloring properties, were less expensive to source, and did not impact the flavor of the products. However, many of these were later found to be quite dangerous and were banned from foods, drugs, and cosmetics.

The Debate

As artificial food dyes can actually mask unhealthy, damaged, or inferior foods, they must be certified by the FDA before usage. Currently there are nine approved artificial or synthetic dyes that are considered safe and are permitted in foods for consumption. However, considerable scientific debate surrounds these additives and how safe they are, especially if consumed in very large doses as is common today. Many studies on artificial food dyes have come back inconclusive, but some animal studies have shown possible links to certain types of cancers.

Negative Behaviors in Children

In the early 1970’s, a pediatric allergist, Dr. Benjamin Feingold, started to suspect that some food additives including artificial colors were causing or worsening negative behaviors such as hyperactivity or inattentiveness in some children. He proposed a diet free of such additives and saw many of his patients improve. This anecdotal finding was later substantiated by many scientific studies which indeed found that artificial food colors exacerbated negative behavioral effects in some children with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

Artificial Colors in the U.K. and the E.U.

In England, the British government extended these studies to normal children and found that synthetic food colors caused negative behavioral effects in some children both with and without ADHD. In response to this mounting evidence, the British government urged food companies to stop using most artificial colors and to find alternative ingredients and undertook to educate the public about the possible side effects of artificial colors on child behavior. The European Union also took action and now requires a warning label on foods containing synthetic color additives. Many food manufacturers in Europe responded to these actions by systematically removing artificial colors and replacing them with natural food dyes such as beet juice extract, paprika, or turmeric.

Artificial Colors in the U.S.

While food manufacturers did this in Europe, they left the artificial colors in the American versions of the exact same products (e.g., M&M’s). Not only do such substitutions improve the nutrition profile of the products, they help to protect the health and development of children. Although there is some cost that goes along with reformulation as well as changes in packaging, it is unclear why those changes were not extended to the US market.

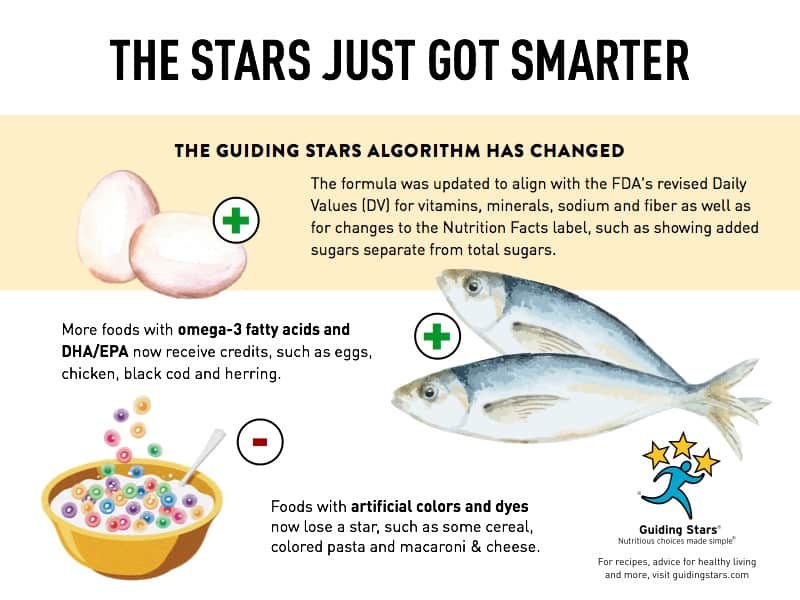

Artificial Colors and Guiding Stars

In response to the growing evidence demonstrating the negative effects of artificial colors on children, the Guiding Stars Scientific Advisory Panel recently decided to debit foods containing artificial colors by 1 star rating. There is no need for artificial colors to be in foods: they are there strictly for cosmetic purposes. There are many natural and safe food dyes that can be used in their place. Guiding Stars hopes to encourage food manufacturers to make the switch and improve the nutritional quality of their products. Artificial colors are also a marker of lower quality foods containing lower quality ingredients and chemical additives. Guiding Stars aims to promote the health of all of its consumers, especially the youngest ones.

Resources

Stevens LJ, Kuczek T, Burgess JR, Stochelski MA, Arnold LE, Galland L. Mechanisms of behavioral, atopic, and other reactions to artificial food colors in children. Nutr Rev. 2013 May;71(5):268-81.

Arnold LE, Lofthouse N, Hurt E. Artificial Food Colors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Symptoms: Conclusions to Dye for. Neurotherapeutics. 2012 Jul; 9(3): 599–609.

Bateman B, Warner JO, Hutchinson E, et al. e e ects of a double blind, placebo controlled, arti cial food colourings and benzoate preservative challenge on hyperactivity in a general population sample of pre- school children. Arch Dis Child, 2004; 89:506-11.

McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A, et al. Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. e Lancet. 2007, Nov. 3; 370:1560–7.